Plein Air Painting: Tips, Tools and Tricks

What Fuels Your Art?

This article is the first of a series of three articles by Renee Rondon .

Our ambition to paint may be fueled by many different things. This includes classes, friends, magazines, YouTube videos, or even a natural joy at just putting brush-to-paint-to-canvas, paper and other materials. No matter where we paint - in a studio, garage or barn, or the shed out back - we just can’t stop!

However, it’s another story when painting plein air! Outside we’re inspired by the scenic landscapes, the smell of grass and flowers, and the wonderful compositions available. We are inundated by nature! There are a few considerations, though, that will help make the whole outdoor experience go much smoother and keep you “fueled” to continue with the plein air method.

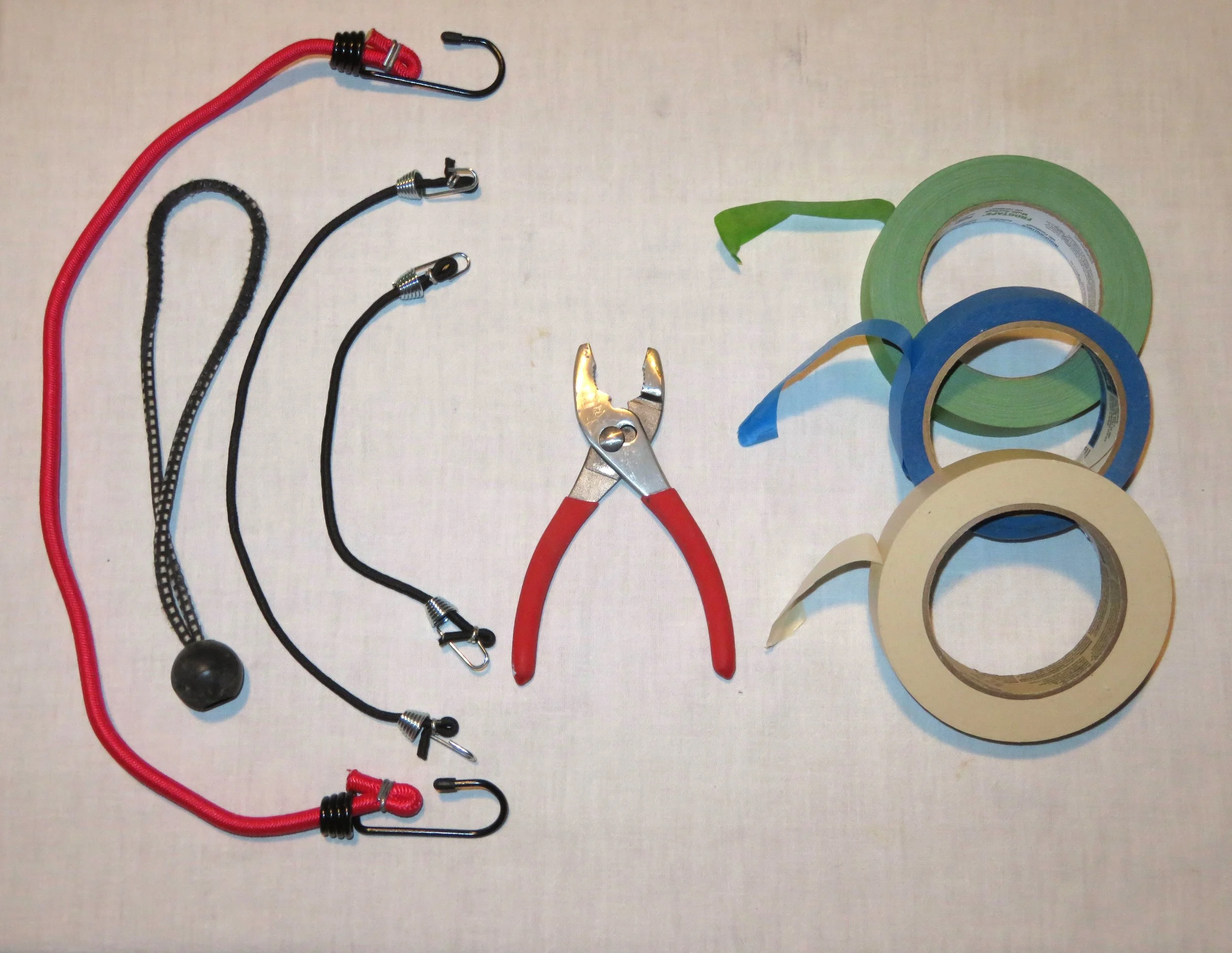

Bungee cords in various sizes, pliers, and masking tape are some of the essential tools I bring in my plein air painting kit.

First, let’s talk about a few tools that will make your plein air journey more successful. There are tools I bring in my outdoor kit that are truly indispensable. One tool is a pair of pliers and a few tiny bungee cords. As you probably know, pliers are often needed to open stuck paint tube caps and other items. A small pair will do, nothing too large needed for this. It does pay to have a pair with rubber or painted handles (red or another bright color). That way when they fall on the grass, you have a better chance of finding them!

As for the bungee cords, I carry several of various sizes with me, as they come in handy for quite a few challenges. Mine are approximately 6 to 15 inches long. They work well to quickly hook a small garbage bag, umbrella or other objects to your easel. The weather is always unpredictable, and gusts of wind can wreak havoc with your setup.

The last tool I’ll mention here is blue tape (or masking tape). This is indispensable for anchoring canvasses, sketches, and sometimes even broken parts on an easel. Don’t leave home without it!

Let’s take a moment to go back in time. Artists have been painting and sketching outdoors for thousands of years, but it hasn’t always been easy. The ancient petroglyphs that were made in caves and on boulders told the location of rivers, hunting areas and other information that helped traveling tribes to navigate. Back then this was an essential tool, not the fun and inspiring reason for modern plein air painting. They either scribed into these hard surfaces or had basic types of paint made from plants and minerals. Evidence has been found of types of oil and watercolor paint that were used many thousands of years ago.

Jumping forward to the 1600s, artists were not thought highly of at all. In fact, they were often relegated to the working labor class. They were thought of as “having dirty hands” (*) and “of only manual labor” (*) until academic schools began teaching the arts. However, they only taught what was thought of as intellectually acceptable. This included mathematics, geometry for spatial dimension, and drawing. Color was not yet taught as it was thought to be vulgar and dirty, having to do with the senses. This was not acceptable in the intellectual world. (*)

In the 1700s artists continued to sketch outdoors and were beginning to see the benefit of art created in nature. In the early 1800s more artists wanted to paint outdoors, but carrying paint was too big a burden when they had to make it on sight. The invention in 1841 by John G. Rand (from America)(†) of paint in tubes was a game-changer for artists back then. Many of the first plein air painters were in France, Italy, and America.

Plein air painting influenced various traditional styles, and began the evolution of Impressionism.

Academic schools that concentrated in art began appearing, such as the École des Beaux and the Barbizon School. The Barbizon School began with artists such as Manet, Degas, Rousseau, Daubigny and others. They started the movement that led art into new realistic, romantic and impressionist styles.(*) Their knowledge, skills and ideas about creating new methods in painting were a big part of the modernization of art. These artists (and others) also were famous for holding the first exhibition of impressionistic art in 1874.(†)

Due to the invention of tubes of paint, artists began rethinking what the purpose of some of the old schools of thought were. Painting outdoors was the beginning of the “study of colors.” Artists began looking at the use of “purer colors” (†) to portray more natural lighting, values, and colors in a fresh way.(‡) As a plein air painter, I do enjoy learning and sharing the history behind plein air painting. It makes me truly grateful for the many choices of tools and equipment available today to make plein air a great experience.

Finally, a true to life story I’d like to share with you. While in a plein air class in Rockport, Maine, we were all scattered around a cove with a quirky pier, deep green trees, and a few boats. A wonderfully fetching scene! After a demonstration from our instructor, we got our easels and paints set up. We began painting. The wind started whipping around. I thought my setup was pretty stable. Nope! Off flew my canvas! Off flew my palette paper! I was standing in dry grass, and everything ended up with dried grass, twigs and bugs on them. Not to be deterred, I staunchly put everything back and started painting again. Nope! Again, the wind was messing with the canvas and palette paper. Luckily someone had blue tape, and I got it all anchored down. I now carry blue tape and bungee cords on every trip. So, what fuels my plein air painting trips? Nature and the outdoors, always. But also, being more prepared and equipped to handle the many challenges of painting outdoors.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this article and continue to enjoy plein air painting.

Please look for my second article in February, The Hopes & Challenges Of Plein Air Painting.

Thank you!

Renée Rondon

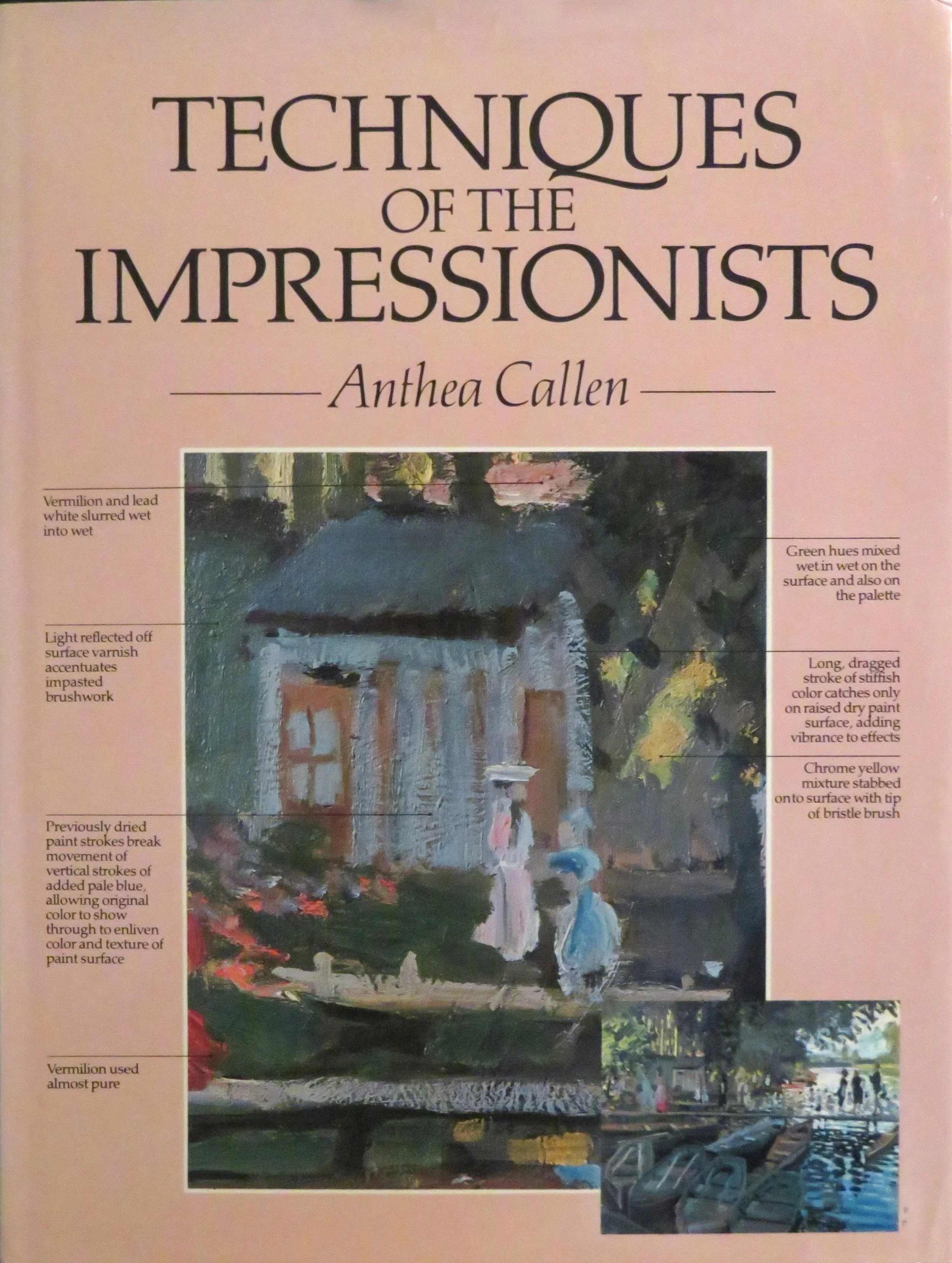

(*) Anthea Callen, Techniques of the Impressionists.

(†) Wikipedia.

(‡) David Bomford, Jo Kirby, John Leighton and Ashok Roy, Art in the Making – Impressionism.